Africa has been at the centre of a growing number of tower sale and lease-back announcements in recent years, with such arrangements typically involving the sale of the passive elements of network operators’ infrastructure. Initially it appeared to be an emerging business model that benefitted all parties, though the recent insolvency issues of some tower operators raises questions whether the model is as compelling in the long-term as it was initially made out to be

IHS’ Darwish suggests selling and leasing back towers offers significant cost savings, as the operator no longer has to incur the cost of running infrastructure

At the end of July it was announced that South Africa based mobile towers infrastructure operator, Africa Cellular Towers had been served with a liquidation order by a high court in South Africa after failing to stave off bankruptcy.

The company had struggled against rising debts and falling revenues for the past year, and a few months ago an unnamed creditor started proceedings against it.

The fortunes of Africa Cellular Towers contrast sharply with the wave of tower deals between mobile network operators and independent tower companies that have made the headlines in Africa in the last few years.

In August, for example, MTN South African was reported to be considering selling off up to half of its towers network following successful sales by its operations in Ghana and Uganda. MTN owns around 6,000 towers in South Africa.

MTN South Africa’s managing director, Karel Pienaar commented that the motivation behind any such sale would be a move to improve the efficiency of the operator’s capital structure, arguing that infrastructure on the ground is not a mobile operator’s core focus, and as such could be better leveraged by a third-party.

At the beginning of this year, Etisalat Group was reported to be mulling bids to sell its towers network in Africa. The telco has subsidiaries in 10 countries on the continent and owned and operated around 4,500 towers at the time.

Etisalat was reported to have been looking to sell the towers to a tower company for approximately US$500 million, but sources indicated that a block sale of the entire portfolio proved difficult prompting the telco to consider a sale on a per-country basis.

Last year, American Tower Corporation announced the completion of the acquisition of approximately 960 existing towers from South African mobile network operator, Cell C for an aggregate purchase price of approximately US$140 million. At the time, American Tower said it expected to acquire from Cell C approximately 440 additional existing towers during the year for an aggregate purchase price of approximately US$60 million.

The tower company was also looking to acquire up to an additional 1,800 towers that were either under construction or would be constructed over the next three years for an additional aggregate purchase price of up to approximately US$230 million.

“The tower deals that we have been witnessing generate value for all parties, in part because of the different set of expectations held by telco operators and tower companies, particularly in developing markets,” explains Javier Gonzalez Piñal, partner at Oliver Wyman management consultancy in Dubai. “Operators tend to value the one-off cash payment resulting from the transaction itself. As margins decline and cash flow is stretched, operators appreciate the opportunity to monetise non-core assets above the long-term reduction of the total cost of ownership over 10 or 15 years.”

IHS is a Nigeria-based tower company that has been successful in appealing to the expectations of mobile network operators in Africa having last year secured an equity investment from the World Bank Group’s IFC, along with co-investors Investec and FMO, to help the company build and acquire mobile phone towers in sub-Saharan Africa.

IHS is the largest telecommunications infrastructure provider in West Africa and in August 2011 it went on to announce that Nigerian CDMA network operator Visafone Communications had agreed to sell and lease-back 459 towers for an undisclosed amount.

“It is estimated that towers account for almost 50 per cent of the total capex of a mobile operator and the associated costs of running and maintaining the towers could increase this to 60 per cent, IHS CEO Issam Darwish told Comm. “Selling and leasing-back may offer significant cost savings, as the operator no longer has to incur the cost of running towers.”

Darwish believes the offerings from the various tower companies vying for business in Africa are pretty uniform. In summary, he described the roles of a tower infrastructure company as follows: site planning, bearing in mind the network rollout plans of prospective customers; obtaining of necessary regulatory approvals; erection and commissioning of tower and the relevant equipment; provision of support services such as back-up power, air-conditioning and security; and the provision of turnkey solutions to telecom companies such as sourcing of equipment, testing and maintenance.

For its part, IHS has been in the sub-Saharan African tower market with operations in Nigeria, Sudan, Kenya and Ghana for a little over a decade and although it began by building towers on behalf of mobile operators, the company has now expanded its offering to building buy-to-let towers as well.

IHS has expanded rapidly in recent years, with revenues surging nearly 50 per cent between 2009 and 2010, from US$70 million to US$107 million. The company employs over 1,000 people who have built more than 2,000 sites; managed more than 4,000 sites; owns 900 co-location sites and provides best-in-class service with uptime of more than 99.95 per cent.

According to Oliver Wyman’s Piñal, the success of IHS and other tower companies like it is based on a simple economic model:

· Operators sell part of their passive assets to a professional tower company. That company optimises processes to reduce total cost of ownership. Operators receive a part of their expected return in the form of a lump sum (typically cash) payment.

· The tower company combines the stable cash flow it receives from the reference tenant (the selling operator) with the upside from additional clients (competing operators) co-locating in the same towers to increase the value of the assets purchased.

· Typically, the deal also includes a financial partner that, in exchange for an initial cash injection, leverages the stable cash flow (operators’ rent) and a higher asset valuation at exit (through the co-location of multiple tenants) to obtain rates of return of 20 per cent – 30 per cent, and sometimes even higher.

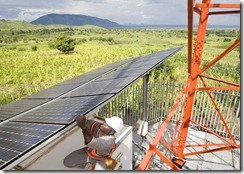

Tower companies are planning to deploy multi-operator solar powered cell sites in a bid to slash their diesel consumption significantly in the coming years

“In every tower deal, the price per tower is the key metric,” Piñal explains. “It must be high enough to provide compensation to the seller but low enough to offer upside for the buyer. This factor is driven by local conditions such as country-specific capex requirements and current opex levels to run the infrastructure. In emerging markets, it has been remarkably stable, at around US$100,000 per tower.”

In a recent interview Charles Green, co-founder and CEO of another of Africa’s burgeoning tower companies, Helios Towers Africa, described the appeal of companies such as his in allowing operators to focus on what they do best, servicing customers rather than managing infrastructure.

This advantage, Green described, enables operators to increase coverage and capacity quickly, without bearing the operational risk or long-term capital requirements. It also has potentially significant positive implications for the industry’s carbon footprint.

The outsourcing of telecom infrastructure management is increasingly commonplace with 50 per cent of towers in the US and 60 per cent in India now run by independent companies. Operators are facing increasing competition, falling revenues per user and need to reduce opex and capex, and independent tower companies provide a solution to them, Green said.

Piñal suggests other traditional value drivers post-tower transaction, such as the tenancy ratios, or the expected opex savings, seem to be “nice to have” for the operators but not essential, and are often left to be enjoyed by the shareholders of the tower company, and are not necessarily discounted in the initial selling price paid to the network operator.

“There are several possible reasons why operators hold such low expectations on the value maximisation capabilities of the tower company post-transaction,” Piñal states. “An opex improvement might be more difficult to achieve for international tower specialists in emerging markets (with limited local presence) than for the telco players that have been operating these networks for many years. Also, high co-location ratios could be more difficult to obtain in less mature markets,” he adds.

Oliver Wyman still contends, however, that operators are satisfied when they off load their balance sheets and generate a positive impact on the debt position. The improvement to their financial position is enough of a benefit that they do not really mind leaving the upside to the shareholders of the tower company itself.

Looking ahead, Darwish forecasts strong growth prospects for the independent tower companies that continue to exercise and deliver on the right economic models. In his opinion, there are almost 100,000 towers in Africa currently, with independent operators owning around 8,000 amongst them, while mobile operators own the rest. “Over the next five years another 30,000 to 50,000 towers will need to be constructed in Africa to keep up with demand and most of this will be done by independent tower companies while simultaneously mobile operators will continue to sell their tower portfolios to independent tower companies like IHS.”

0 comments ↓

There are no comments yet...Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment